Hemolytic Anemia from Medications: Recognizing Red Blood Cell Destruction

Medication Risk Checker for Hemolytic Anemia

Check Medication Risks for Hemolytic Anemia

This tool identifies medications that may cause drug-induced immune hemolytic anemia (DIIHA). Select your current medications to see if they pose a risk.

Select Your Medications

Your Risk Assessment

Select medications to see your risk level

When a medication you’ve been taking suddenly starts destroying your red blood cells, it’s not just a side effect-it’s a medical emergency. Drug-induced immune hemolytic anemia (DIIHA) doesn’t come with a warning label. It sneaks in after days or weeks of normal use, and by the time you feel it, your body is already in crisis. Fatigue, shortness of breath, yellowing skin-these aren’t just signs of being tired. They’re signs your red blood cells are being torn apart faster than your body can replace them.

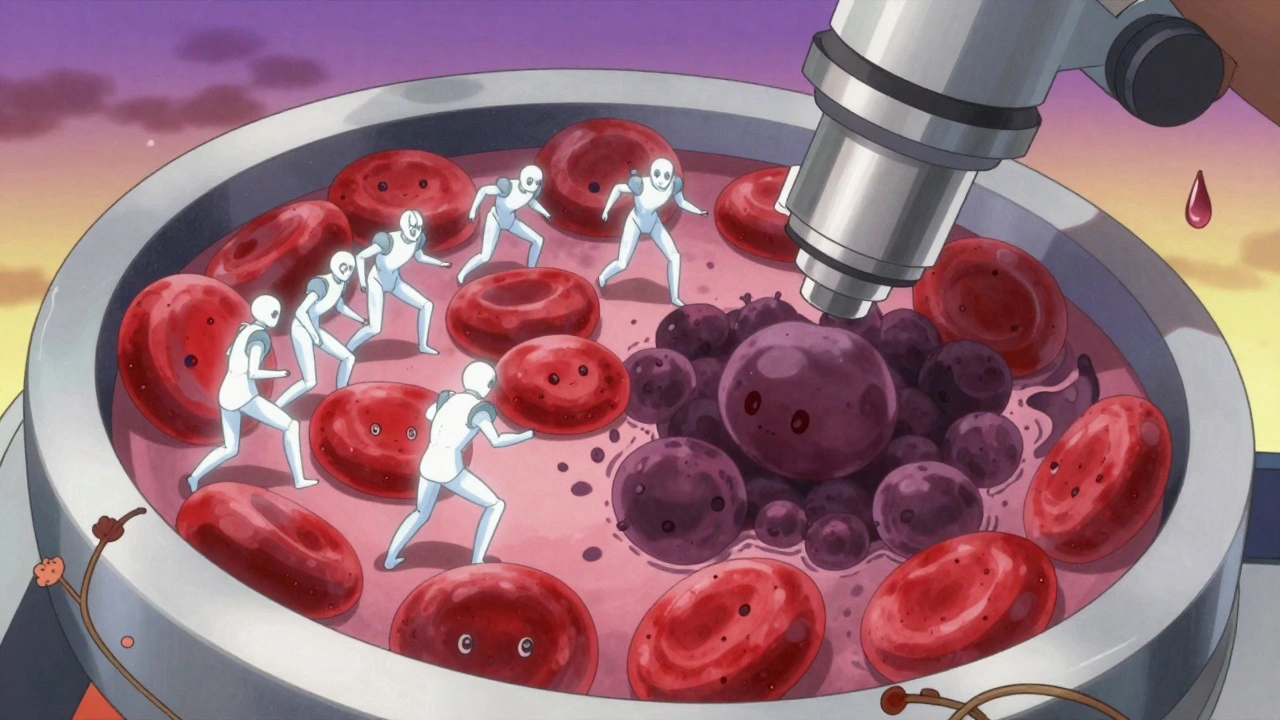

How Medications Trigger Red Blood Cell Destruction

Your red blood cells normally live about 120 days. In DIIHA, that lifespan gets cut down to hours or days. This isn’t random. It’s your own immune system turning on your blood. Some drugs, like ceftriaxone, cefotetan, and piperacillin, bind to the surface of red blood cells. Your immune system sees this as a foreign invader and sends antibodies to destroy them. This is called immune-mediated hemolysis. It usually takes 7 to 10 days of continuous drug use before your body builds up enough antibodies to cause trouble.

There’s another way drugs wreck red blood cells-through oxidation. Certain medications, including dapsone, phenazopyridine, and nitrofurantoin, produce free radicals that damage hemoglobin. This leads to clumps called Heinz bodies inside red blood cells. These damaged cells get trapped and destroyed in the spleen. This form hits hardest in people with G6PD deficiency, a genetic condition affecting 10-14% of African American men and 4-15% of Mediterranean populations. Even if you’ve never had symptoms before, one dose of the wrong drug can trigger a sudden, severe drop in hemoglobin.

Which Medications Are Most Likely to Cause This?

Not all drugs carry this risk, but some are far more dangerous than others. Cephalosporins-especially third-generation ones like ceftriaxone and cefotetan-are responsible for about 70% of immune-mediated cases. Penicillin and its derivatives still show up, but less often now that they’re used less frequently. NSAIDs like ibuprofen and naproxen can also cause it, though rarely.

For oxidative hemolysis, the list is longer and more surprising:

- Dapsone (used for leprosy and skin conditions)

- Phenazopyridine (Pyridium, for urinary pain)

- Ribavirin (for hepatitis C)

- Amoxicillin-clavulanate

- Primaquine (for malaria prevention)

- Sulfa drugs

- Topical benzocaine (in throat sprays and numbing gels)

- Butyl nitrate and amyl nitrate (“poppers”)

Methyldopa used to be a top offender, but it’s rarely prescribed today. Still, if you’re on an older medication or have been taking something for years, don’t assume it’s safe. The risk doesn’t go away with time-it just hides.

What Symptoms Should You Watch For?

The early signs are easy to miss. You might think you’re just run down from work, stressed, or coming down with the flu. But if you’re feeling unusually tired (92% of cases), weak (87%), short of breath (76%), or notice your skin or eyes turning yellow (81%), it’s not normal. Your heart may race-over 100 beats per minute-because your body is trying to pump more blood to make up for the lost oxygen.

Physical signs include pale skin, dark urine (from hemoglobin breakdown), and sometimes abdominal or back pain. In severe cases, you might feel dizzy, confused, or faint. These aren’t just uncomfortable-they’re warning signs your organs are starved of oxygen.

What makes DIIHA tricky is that symptoms can appear suddenly. One day you’re fine. The next, you’re in the ER. A 2024 study found that 43% of cases were misdiagnosed at first-often as infections, liver problems, or even depression.

How Doctors Diagnose It

There’s no single test. Diagnosis requires piecing together symptoms, medication history, and lab results. Your doctor will look for three key markers:

- Elevated indirect bilirubin (>3 mg/dL) - from broken-down hemoglobin

- High LDH (>250 U/L) - released when red blood cells burst

- Low haptoglobin (<25 mg/dL) - a protein that binds free hemoglobin and gets used up

A peripheral blood smear is critical. If you see spherocytes (small, round red cells without the normal dip), it points to immune destruction. If you see Heinz bodies (dark clumps inside red cells), it’s oxidative damage.

The direct antiglobulin test (DAT) checks for antibodies stuck to your red blood cells. It’s positive in 95% of immune-mediated cases-but not always. If the drug is still in your system or if the antibody is weak, the test can be negative. That doesn’t rule out DIIHA.

For suspected G6PD deficiency, testing is tricky. During active hemolysis, your body is producing new red blood cells (reticulocytes) that still have normal enzyme levels. This can give a false negative. The best time to test is 2-3 months after the episode, when your red blood cell population has reset.

What Happens If It’s Not Treated?

Left unchecked, DIIHA can be deadly. A rapid drop in hemoglobin-3 to 5 g/dL in just 72 hours-can overload your heart. Studies show that when hemoglobin falls below 6 g/dL, 22% of patients develop arrhythmias, 15% get cardiomyopathy, and 8% go into heart failure. This isn’t theoretical. It’s documented in real patients who didn’t get help fast enough.

There’s another hidden danger: blood clots. Even though you’re losing blood, your body enters a hypercoagulable state. A 2023 study found 34% of severe DIIHA cases developed venous thromboembolism-deep vein clots or pulmonary embolisms. That’s why doctors often give blood thinners even while treating the anemia.

How It’s Treated

The first and most important step? Stop the drug. Immediately. No exceptions. In most cases, hemoglobin levels stabilize within 7-10 days after stopping the medication. Full recovery usually takes 4-6 weeks.

If your hemoglobin drops below 7-8 g/dL or you’re having severe symptoms like chest pain or trouble breathing, you’ll need a blood transfusion. But transfusions aren’t always simple. You might need special cross-matching because your blood is full of antibodies.

Corticosteroids like prednisone were once standard, but their benefit is unclear. Many patients recover just by stopping the drug. They’re only used if hemolysis continues after drug removal.

If your body keeps making antibodies even after the drug is gone (drug-independent autoantibodies), you’ll need stronger treatment. Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) at 1 g/kg/day for two days can block the immune attack. If that doesn’t work, rituximab (given weekly for four weeks) shuts down the antibody-producing cells. About 78% of these stubborn cases respond within 3-6 weeks.

For oxidative damage with methemoglobinemia (when hemoglobin can’t carry oxygen), methylene blue is life-saving-but only if you don’t have G6PD deficiency. In those patients, methylene blue can make things worse, triggering even more hemolysis. Alternative treatments like ascorbic acid or exchange transfusion are used instead.

What You Can Do to Stay Safe

If you’ve ever had unexplained anemia, jaundice, or dark urine after starting a new medication, tell your doctor. Keep a list of all drugs you’ve taken-even over-the-counter ones. If you’re of African, Mediterranean, or Southeast Asian descent, ask about G6PD testing before taking any new medication.

Hospitals are starting to use electronic alerts to flag high-risk drugs for patients with known risk factors. But you’re your own best advocate. If you’re on one of the drugs listed above and start feeling unusually tired or yellow, don’t wait. Get your blood checked.

And if you’ve had DIIHA once? Never take the same drug again. Cross-reference all future prescriptions with your history. Even a small dose can trigger a recurrence.

Why This Matters

Drug-induced hemolytic anemia is rare-but it’s not rare enough. With over 100 medications linked to oxidative damage and dozens more tied to immune destruction, it’s a silent threat in everyday prescriptions. Most doctors aren’t trained to spot it quickly. Patients aren’t warned. But the data is clear: early recognition saves lives.

Recovery is almost guaranteed if caught in time. But delay, and you risk permanent heart damage, blood clots, or worse. The next time you pick up a prescription, ask: Could this be one of the ones that attacks my blood? It’s not paranoia. It’s prevention.

Can you get drug-induced hemolytic anemia from over-the-counter drugs?

Yes. While most cases come from prescription drugs, over-the-counter medications like NSAIDs (ibuprofen, naproxen) and topical benzocaine (in throat sprays or numbing gels) have been linked to hemolytic anemia. Even common pain relievers can trigger immune reactions in rare cases, especially with prolonged use. If you develop unexplained fatigue or jaundice after starting any new OTC drug, stop it and see a doctor.

Is G6PD deficiency the only reason for oxidative hemolysis?

No. While G6PD deficiency makes you far more vulnerable, oxidative hemolysis can happen even in people with normal G6PD levels. Drugs like dapsone, phenazopyridine, and ribavirin can directly damage hemoglobin through oxidant effects, regardless of your genetic status. That’s why doctors warn against these drugs even for people without known deficiencies.

How long after taking a drug does hemolytic anemia start?

It depends on the mechanism. Immune-mediated cases usually take 7-10 days of continuous use because your body needs time to build antibodies. Oxidative hemolysis can hit within 24-72 hours, especially in G6PD-deficient individuals. In rare cases, a single dose of a high-risk drug can trigger a rapid reaction.

Can children get drug-induced hemolytic anemia?

It’s rare in children, but it does happen. When it does, symptoms are often more severe. A 2023 pediatric study found children with DIIHA had average hemoglobin levels of 5.2 g/dL-lower than the adult average of 6.8 g/dL. Because kids are less likely to report vague symptoms like fatigue, diagnosis is often delayed. Always mention any new medications to your child’s pediatrician if they develop unexplained pallor, jaundice, or dark urine.

Will I always be at risk if I’ve had it once?

Yes. Once you’ve had drug-induced hemolytic anemia from a specific medication, you’re at high risk for a recurrence-even with a tiny dose. You must avoid that drug-and often entire drug classes-forever. Keep a medical alert card or note in your phone listing the drugs that caused your reaction. Share this list with every new doctor you see.

Are there new treatments on the horizon?

Yes. Two 2024 clinical trials are showing promise. One (NCT05678901) tested efgartigimod, a drug that clears antibodies from the blood, and saw a 67% response rate in DIIHA patients within four weeks. Another (NCT05812345) is studying complement inhibitors, which block a key part of the immune attack on red blood cells. These could offer new options for patients who don’t respond to steroids or rituximab.

Ashley Farmer

December 8, 2025 AT 17:13I had a friend go through this with ceftriaxone after a surgery. She thought she was just tired from recovery, but her hemoglobin dropped so fast they had to transfuse her. No one warned her about it-even her pharmacist didn’t mention it. If you’re on any antibiotics long-term, please get a baseline CBC. It’s not dramatic, but it could save your life.

Also, if you’re G6PD deficient, ask your doctor before taking *anything* with 'sulfa' or 'nitro' in the name. Even OTC stuff like phenazopyridine can sneak up on you.

So many people think 'it's just a side effect' until they’re in the ER. Please, just be curious about your meds.

Love you all. Stay safe.

David Brooks

December 9, 2025 AT 13:42OMG I JUST HAD THIS HAPPEN TO ME LAST MONTH 😭 I was on dapsone for a skin rash and woke up one morning looking like a ghost. My urine was brown. I thought I was dying. Went to urgent care and they thought it was a UTI. Took 3 days and a blood test to figure out it was HEMOLYSIS. They told me I was lucky I didn’t have a stroke. I’m still shaking thinking about it.

EVERYONE WHO TAKES DAPSONE: READ THIS POST. SAVE YOURSELF. I’m telling my whole family now. This needs to be on every pharmacy label.

Jennifer Anderson

December 11, 2025 AT 10:52ok so i just found out my mom is on primaquine for travel and she’s g6pd deficient but no one told her?? like… how?? i’m calling her right now. also phenazopyridine?? i used that for my uti last year and felt weirdly tired for a week but i just thought i was stressed. this is wild. i’m sharing this everywhere. also, typo? i think u meant ‘haptoglobin’ not ‘haptoglobin’ lol

Sadie Nastor

December 12, 2025 AT 18:54Thank you for writing this. I’ve been scared to take any new meds since my cousin had a bad reaction to amoxicillin-clavulanate. I didn’t even know it could do this. I just thought it was ‘allergies’ or ‘side effects.’

Now I’m going to print this out and keep it with my meds list. Also… 🫂

Can we get a simple one-pager for patients? Like, ‘Medications That Can Destroy Your Blood Cells (And What To Do)’? I’d use that. I think so many people don’t know this is even a thing.

Also, I’m so glad you mentioned benzocaine. I used that spray for my sore throat last winter. I felt fine, but now I’m wondering…

Thank you. Really. This matters.

Nicholas Heer

December 14, 2025 AT 05:19THIS IS A BIG PHARMA COVERUP. THEY KNOW. THEY KNOW THESE DRUGS ARE KILLING PEOPLE. WHY AREN’T THEY BANNED?? Ceftriaxone is in EVERY hospital. Dapsone? Prescribed like candy. And don’t get me started on nitro poppers-those are sold in gas stations like candy. WHO’S PAYING FOR THESE LAB TESTS WHEN PEOPLE DROP DEAD??

It’s not ‘rare.’ It’s being hidden. The CDC won’t track it because it’s ‘too expensive.’ The FDA doesn’t mandate warnings because ‘it’s rare.’ But it’s NOT rare if you’re Black, Mediterranean, or poor. This is systemic neglect. They don’t care about us.

Also, who’s funding this post? I’m suspicious. Why now? Is this a vaccine distraction? I’m not buying it.

Sangram Lavte

December 14, 2025 AT 09:50This is very informative. I work in a clinic in India and we see G6PD deficiency often. Many patients come in with dark urine after taking sulfa drugs or antimalarials. We test for it routinely now, but in rural areas, no one knows. I wish we had a simple chart like this to hand out. Also, benzocaine sprays are sold over the counter here too. People use them for kids’ teething. This needs to be in local languages.

Thank you for the detailed breakdown. I’ll share this with my colleagues.

Oliver Damon

December 15, 2025 AT 08:41The immunological mechanism described here is textbook immune-mediated hemolysis-haptenization of RBC membranes by beta-lactams leading to IgG-mediated opsonization. But the oxidative pathway is even more insidious: NADPH depletion in G6PD-deficient erythrocytes prevents detoxification of ROS, leading to Heinz body formation and splenic sequestration.

What’s underdiscussed is the delayed presentation window. The immune response isn’t immediate-it requires clonal expansion of B-cells producing IgG against drug-RBC complexes. That’s why symptoms appear after 7–10 days. This isn’t an allergy. It’s an autoimmune cascade triggered by a xenobiotic.

And yes, the diagnostic triad-low haptoglobin, elevated LDH, elevated indirect bilirubin-is pathognomonic. But we often miss the history. Patients don’t connect ‘I took a new antibiotic’ to ‘I feel like I’m suffocating.’ We need better patient education tools. This post is a start.

Ryan Sullivan

December 16, 2025 AT 00:53Pathetic. You wrote a 1,200-word essay on a condition that affects 1 in 10,000 people and called it an emergency. Meanwhile, 300,000 Americans die annually from opioid overdoses and you’re worried about ceftriaxone? This is fearmongering dressed as medicine. You didn’t even mention that most cases resolve after discontinuation. The real emergency is people like you turning every minor side effect into a conspiracy. Grow up.