Color Blindness: Understanding Red-Green Defects and How They’re Passed Down

Most people think color blindness means seeing the world in black and white. But for the vast majority of people with this condition, it’s not about missing color entirely-it’s about mixing up reds and greens. Think of a red apple next to a green leaf. To someone with normal vision, the difference is obvious. To someone with red-green color blindness, they might look almost identical. This isn’t a flaw in their eyesight-it’s a genetic quirk, passed down through families in a way that explains why it’s far more common in men than women.

What Exactly Is Red-Green Color Blindness?

Red-green color blindness isn’t one single condition. It’s a group of related vision differences caused by problems with the light-sensitive pigments in your eyes’ cone cells. These cones come in three types: one for red light, one for green, and one for blue. When the red or green cones don’t work right, your brain gets mixed signals. That’s when reds look dull, greens turn brownish, and oranges and yellows start to blend together.

The two most common forms are deuteranomaly and protanopia. Deuteranomaly means your green cones are faulty but still somewhat functional. It’s the most common type, affecting about 5% of men. Protanopia means you’re missing your red cones entirely. That’s rarer, but it makes reds look darker and more like black or gray. There’s also protanomaly (weak red cones) and deuteranopia (no green cones), but these are less frequent.

What’s surprising is that most people with this condition don’t even realize they’re different until they’re tested. A child might pick the wrong crayon in art class. An adult might struggle to tell if a tomato is ripe or if a traffic light is red or green. Many learn to adapt-using brightness, position, or context instead of color alone.

Why Is It More Common in Men?

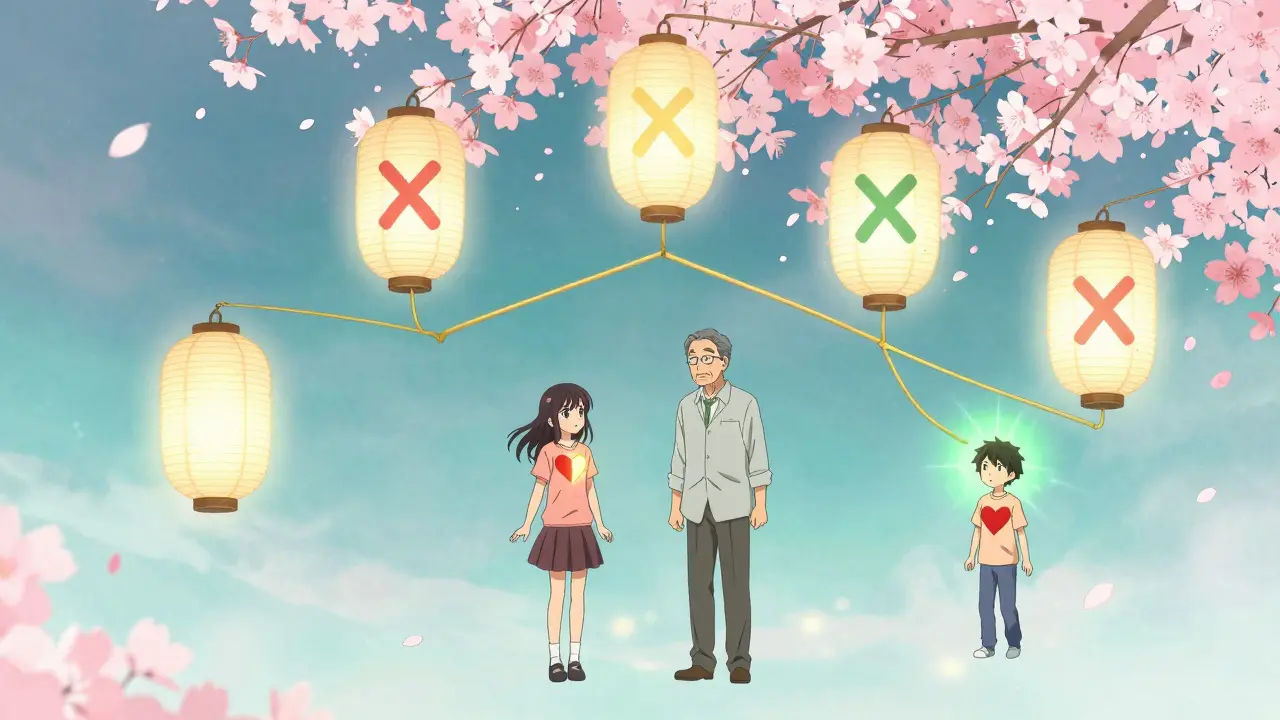

The reason men are affected far more often than women comes down to biology-and chromosomes. The genes that make the red and green pigments are located on the X chromosome. Men have one X and one Y chromosome. Women have two X chromosomes.

If a man inherits an X chromosome with a faulty color vision gene, he has no backup. His Y chromosome doesn’t carry a replacement. So he’ll have color blindness. But a woman needs two faulty copies-one on each X chromosome-to be affected. That’s rare. Statistically, about 8% of men have some form of red-green color blindness. Only about 0.5% of women do.

This pattern is called X-linked recessive inheritance. It’s the same reason conditions like hemophilia are more common in men. A mother can carry the gene without being affected herself. She can pass it to her sons. If a son inherits the faulty gene, he’ll have the condition. Daughters can inherit it too, but they’ll usually be carriers unless both parents pass on the gene.

How Is It Passed Down? A Family Tree Example

Let’s say a man has red-green color blindness. He passes his X chromosome with the faulty gene to all his daughters-but none of his sons (because sons get his Y chromosome). So all his daughters become carriers. If one of those daughters has a son, there’s a 50% chance he’ll inherit the faulty gene and be color blind.

Now imagine a woman who is a carrier. She has one normal X and one faulty X. Each son has a 50% chance of being color blind. Each daughter has a 50% chance of being a carrier. Only if she has a son who inherits the faulty X and a daughter who inherits the faulty X from both her and her color-blind father will that daughter be affected.

This is why you’ll often see color blindness skip generations. A grandfather might be affected. His daughter isn’t. But her son is. The trait didn’t disappear-it was hidden in the mother.

How Do Scientists Know It’s Genetic?

Back in 1798, John Dalton-yes, the same Dalton who developed atomic theory-wrote about his own trouble seeing red and green. He was one of the first to describe the condition scientifically. Today, we know his symptoms were caused by a mutation in the OPN1LW gene, which controls red pigment production.

Modern genetics has mapped the exact location of these genes: Xq28, on the long arm of the X chromosome. There’s one gene for red (OPN1LW), but multiple copies for green (OPN1MW). These genes sit next to each other in a row. During reproduction, they can accidentally swap parts. That’s how hybrid genes form-genes that are part red, part green-and why some people see colors differently than others.

Studies from the National Eye Institute and the University of Arizona show that the most common cause isn’t a single point mutation. It’s a recombination error-a glitch during sperm or egg formation-that deletes or fuses these pigment genes. That’s why the condition runs in families and doesn’t pop up randomly.

How Is It Tested?

The most famous test is the Ishihara test. It uses plates filled with colored dots that form numbers. People with normal vision see one number. People with red-green color blindness see a different number-or nothing at all. It’s simple, fast, and still used in schools, eye clinics, and even pilot exams.

But it’s not perfect. Some people memorize the patterns. Others with mild forms pass the test but still struggle in real life. That’s why some doctors now use more advanced tools like the Farnsworth-Munsell 100 Hue Test, which asks you to arrange colored caps in order. It’s more precise.

There are also digital tools like Color Oracle and Sim Daltonism. These apps simulate how the world looks to someone with color blindness. Designers use them to make websites, apps, and charts easier to read for everyone.

What Does It Mean in Daily Life?

For most people, color blindness is a minor inconvenience. But in some situations, it can be a real problem.

- Electrical wiring: Red and green wires can be hard to tell apart. Many electricians label wires with numbers or use texture.

- Food: Ripe vs. unripe fruit, cooked vs. raw meat-these distinctions rely on color. People learn to check texture or use thermometers instead.

- Maps and charts: Color-coded graphs can be confusing. Good design uses patterns, labels, or brightness differences too.

- Driving: Traffic lights are usually arranged in the same order (red on top, green on bottom). But in fog or glare, that’s not enough. Some drivers use special filters or rely on the position of the light.

- Clothing: Matching socks or shirts can be a challenge. Many people stick to neutral tones or use apps that identify colors via smartphone cameras.

One Reddit user, a commercial pilot, wrote: “I had 20/20 vision. But I failed the color test. I couldn’t become a pilot-even though I could see the lights fine.” That’s the reality. Some careers still require perfect color vision, even if the person can function well in daily life.

Can It Be Fixed?

No cure exists. You can’t change your genes. But there are tools that help.

EnChroma glasses are the most well-known. They cost between $330 and $500 and use special filters to block certain wavelengths of light. This helps the brain separate red and green signals better. About 80% of users report improved color perception. But they don’t restore normal vision. And they don’t work for everyone-especially those with complete loss of a cone type.

There are also apps and browser extensions that adjust screen colors. Microsoft and Apple both offer built-in color filters in their operating systems. These let you shift colors to make reds and greens stand out more.

And then there’s the future. In 2022, scientists successfully gave color vision to adult squirrel monkeys using gene therapy. They injected a normal human red pigment gene into the monkeys’ eyes. Within weeks, the monkeys could tell red from green for the first time. The effect lasted over two years. It’s early, but it proves the brain can learn to use new color signals-even as an adult.

That doesn’t mean a cure for humans is around the corner. But it does mean that someday, gene therapy might help people with red-green color blindness see the full spectrum.

What’s Being Done to Help?

More than just tech, there’s growing awareness. The Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG 2.1) require websites to use color in ways that don’t rely on it alone. Buttons must have labels. Charts must have patterns. That’s not just good design-it’s the law in many places, including the European Union.

Companies like Adobe offer free plugins like Colorblindifier, which lets designers see how their work looks to someone with color blindness. Over 45,000 people have downloaded it since 2015.

Even public transit systems are adapting. Portugal’s ColorADD system uses simple shapes-like triangles or circles-to label colors on maps and signs. It’s now used in 17 countries.

And legally, in places like the UK, color blindness is recognized as a disability under the Equality Act. Employers must make reasonable adjustments. If someone can’t read a color-coded chart, they’re entitled to a version with labels.

Is It Really a Disability?

Most people with red-green color blindness don’t see it that way. A 2022 survey by Colour Blind Awareness found that 92% consider it a minor inconvenience. Only 37% said they felt embarrassed by color-matching mistakes. Many say it’s just part of who they are.

One graphic designer wrote: “I used to think I was bad at color. Then I learned to use contrast and texture. Now I design better than most people who see color the ‘normal’ way.”

It’s not about seeing less. It’s about seeing differently. And that difference, while genetic, doesn’t have to hold you back.

Can color blindness get worse over time?

No. Red-green color blindness is congenital, meaning you’re born with it. It doesn’t worsen with age, unlike conditions like macular degeneration. Your cone cells don’t degrade. What changes is your ability to adapt. Many people learn to compensate better over time using context, brightness, or tools.

Can women be color blind?

Yes, but it’s rare. A woman needs to inherit the faulty gene from both her mother and father. Since only about 8% of men have it, and women need two copies, the chance is roughly 0.5%. Some women with one faulty gene may notice mild differences in color perception, but they usually don’t meet the clinical definition of color blindness.

Are there different types of red-green color blindness?

Yes. The four main types are: protanopia (no red cones), deuteranopia (no green cones), protanomaly (weak red cones), and deuteranomaly (weak green cones). Deuteranomaly is the most common, affecting about 5% of men. Protanopia is less common but more severe. All four affect how reds and greens are perceived, but the exact experience varies.

Do color-correcting glasses really work?

They can help, but they’re not a cure. Studies show about 80% of users with deuteranomaly or protanomaly report improved color distinction-especially in natural light. But they don’t restore full color vision. They also don’t work for people with complete loss of a cone type. And they’re expensive. For many, learning to use brightness or labels is more practical.

Can I be tested for color blindness at home?

Yes. There are free online tests like the Ishihara test or the Farnsworth D-15 test. But they’re not always accurate. Lighting, screen brightness, and device quality can affect results. For a reliable diagnosis, see an eye doctor who uses standardized tools under controlled conditions.

Brooks Beveridge

December 17, 2025 AT 22:43Man, I never realized how much I take color for granted until I saw my nephew struggle to pick out his red socks from the laundry. He’s 7 and already figured out that the brightest one’s usually red. Smart kid. We don’t call it a disability-we call it his superpower. He sees patterns we miss. And honestly? His art is next level.

It’s not about fixing him. It’s about building a world where he doesn’t have to bend over backward to fit in. We all see the world differently. That’s not broken. That’s beautiful.

Jonathan Morris

December 19, 2025 AT 11:54Actually, the genetic model described here is oversimplified. The OPN1LW and OPN1MW genes are arranged in a tandem array on the X chromosome, and recombination events between them are far more complex than a simple ‘swap.’ Most cases aren’t due to point mutations-they’re due to unequal crossing over, which can delete, fuse, or create hybrid genes. The 8% statistic for men? That’s an average. In some populations, it’s as high as 12%.

Also, the claim that women need two faulty copies is misleading. X-inactivation can cause skewed expression, meaning some female carriers show mild symptoms. This isn’t just genetics-it’s epigenetics too. The article is cute, but it’s not science. It’s a pop bio summary.

Linda Caldwell

December 20, 2025 AT 20:35My brother’s color blind and he’s the best cook in the family. He knows exactly when meat’s done by texture. He picks ripe avocados by feel. He doesn’t need color-he’s got intuition. And honestly? He’s way more confident than most people who think they’re ‘normal.’

Stop seeing it as a deficit. Start seeing it as a different way of seeing. The world needs more people who notice the quiet stuff.

CAROL MUTISO

December 21, 2025 AT 03:59Oh honey, the real tragedy isn’t the color blindness-it’s that we still design everything like everyone sees like we do.

I’ve had to explain to three different UX designers why their ‘purple-on-blue’ button was unreadable. They acted like I was asking them to paint the Mona Lisa with a toothbrush. Meanwhile, my brother’s been using color filters on his phone since 2012 and still gets called ‘weird’ for it.

And don’t get me started on traffic lights. I once saw a guy pull up to a red light… and then honk because he thought it was green. He was wearing a ‘I ❤️ NYC’ shirt. The irony was thicker than his coffee.

It’s not about fixing people. It’s about fixing the damn system. And if we can make a phone that reads your face to unlock it, we can make a traffic light that doesn’t rely on pigment.

Sam Clark

December 21, 2025 AT 21:52While the genetic mechanism described is accurate, it is important to note that the term 'color blindness' is a misnomer. The condition is better described as 'color vision deficiency' (CVD), as most individuals retain the ability to perceive color, albeit with altered spectral sensitivity. The World Health Organization and the International Council of Ophthalmology have recommended this terminology since 2018 to reduce stigma and improve public understanding.

Furthermore, the assertion that color vision deficiency is 'not a disability' is context-dependent. Under the Americans with Disabilities Act, accommodations may be legally required in certain occupational settings, particularly those involving safety-critical color discrimination. Therefore, the social construct of disability must be acknowledged alongside the biological reality.

Chris Van Horn

December 23, 2025 AT 11:22Let me tell you something. This whole post is just woke propaganda dressed up as science. Color blindness? Please. People just don’t want to learn the difference between red and green because they’re too lazy. I’ve seen it-my cousin’s kid couldn’t tell red from green, so the school gave him special crayons. WHAT? Next thing you know, we’ll be printing road signs in Braille for people who can’t read traffic lights.

And don’t get me started on those $500 glasses. You’re telling me we need to spend half a grand so some guy can tell his shirt from his pants? That’s not progress. That’s madness.

And why do women get a free pass? Oh right, because feminism. The article’s just pandering. I’m not buying it.

Virginia Seitz

December 24, 2025 AT 11:08My dad’s color blind. He thinks my purple shirt is blue. I think it’s purple. We both win 😊

amanda s

December 24, 2025 AT 11:35How dare you say this isn’t a disability? My brother lost his job because he couldn’t tell the difference between red and green wires. He almost electrocuted himself. And now you want to call it ‘just a different way of seeing’? That’s not empathy. That’s dangerous nonsense. We need mandatory color-blind-friendly standards in EVERY industry. This isn’t a privilege-it’s a civil rights issue. And if you’re not fighting for it, you’re part of the problem.

Peter Ronai

December 25, 2025 AT 19:51Oh wow. Another article pretending to be educational. Let me guess-this was written by someone who passed an Ishihara test once and now thinks they’re a neuroscientist? You mention gene therapy in monkeys? Cool. But you don’t mention that the monkeys were injected with viral vectors directly into their retinas. That’s not ‘someday for humans.’ That’s ‘maybe in 30 years if we don’t blow up the entire field with regulatory chaos.’

And those EnChroma glasses? They’re a scam. They don’t work for protanopes. They don’t work for deuteranopes with severe loss. They just make colors look weirdly saturated, like a sunset through a cheap filter. I’ve tried them. I’m not impressed. Stop selling hope like it’s a Kickstarter campaign.

Steven Lavoie

December 26, 2025 AT 03:30I’ve worked with color-blind engineers for over a decade. They’re some of the most detail-oriented people I know. They notice when a wire is slightly frayed, when a label is misaligned, when the shade of green on a schematic doesn’t match the component’s datasheet. They don’t see the color-they see the structure.

And honestly? We should be designing systems that work for them, not forcing them to adapt to ours. The real innovation isn’t in glasses or apps-it’s in rethinking how we communicate information. That’s the real lesson here.

Michael Whitaker

December 27, 2025 AT 22:14As a geneticist with a Ph.D. from Stanford, I must point out that the article’s description of X-linked inheritance is technically correct, but the implication that it’s ‘rare’ in women is misleading. The penetrance of X-linked traits is not binary. Due to X-inactivation mosaicism, many female carriers exhibit mild phenotypes-especially in deuteranomaly. These individuals often self-report as ‘normal’ because they can pass Ishihara tests, yet they experience chromatic discrimination deficits in real-world tasks.

Additionally, the claim that color vision deficiency doesn’t worsen with age is misleading. While the cone cell defect is congenital, age-related retinal changes can exacerbate contrast sensitivity, making color discrimination more difficult over time. The article ignores this nuance. Amateur science at its finest.

Anu radha

December 28, 2025 AT 17:40My uncle in India can’t tell red from green. He’s a teacher. He uses numbers on his chalkboard. He says, ‘Color is nice, but understanding is better.’

He’s my hero.

Jigar shah

December 30, 2025 AT 11:21Interesting. But I wonder-what about the evolutionary advantage? Some studies suggest that red-green color vision deficiency might have helped our ancestors spot camouflaged prey or edible plants in dappled forest light. Maybe it’s not a defect. Maybe it’s a trade-off. We lost some color, but gained better motion detection in low contrast. Evolution doesn’t care about traffic lights. It cares about survival.

Naomi Lopez

January 1, 2026 AT 04:18Ugh. Another ‘color blindness is cool’ post. Can we please stop romanticizing disability? My cousin is color blind and he can’t work in aviation, design, or electrical engineering. He’s got a degree in sociology and works at a call center. He’s smart. He’s capable. But the system doesn’t care. It just says ‘no’ because of a test he didn’t fail-he was born with a different biology.

Stop calling it a superpower. It’s a barrier. And we’re the ones building the walls.

Jane Wei

January 2, 2026 AT 08:27My roommate’s color blind. He once wore mismatched shoes for a week and didn’t notice. I didn’t say anything. He’s got a killer sense of humor. We just laugh about it.

Also, he’s the only one who can find the hidden number in Ishihara plates. Weird, right?